Virtual Chemotherapy

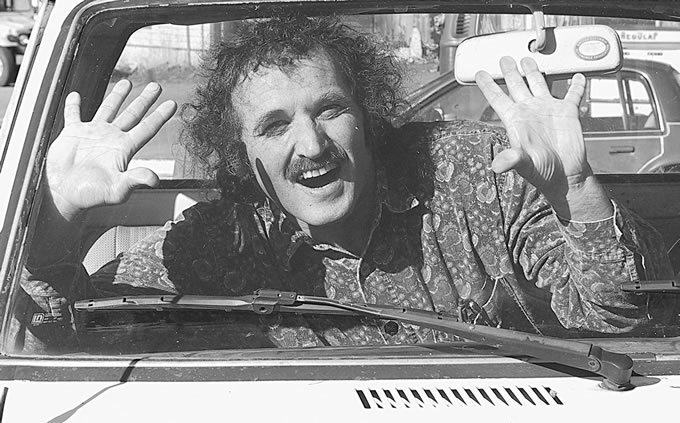

Shilo Zylbergold | Best Medicine

image by: Rhoda Baer

Chemotherapy is just medieval. It's such a blunt instrument. We're going to look back on it like we do the dark ages - Eric Topol

Today, whether you want to or not, you are coming along for a ride to my chemotherapy session. You’re welcome. You might call this a virtual chemo experience.

First, we have to catch the ferry from our island home across the water to “the big smoke” and then drive about forty minutes to the Cancer Agency building at the Royal Jubilee Hospital. We know we have to get to the ferry early, just in case there’s an overload. What makes this tolerable is the knowledge that we can put our vehicle in the ferry lineup and then enjoy the wait sipping on a cuppa java and possibly a cinnamon bun at the local cafe. Are we having fun yet?

Approximately ninety minutes later we pull into the parking lot at the Cancer Agency. We search hard for an empty stall and are amazed at how full the lot is. We shouldn’t be that surprised, as cancer seems to be ubiquitous these days and either affects someone in our family or in the families of our friends and neighbours. There are no six degrees of separation when it comes to cancer.

After a bit of circling, we spot a vehicle pulling out of a parking space and immediately take its place. As we approach the Cancer Agency building we fumble in our pockets for some loose change to deposit in the pay parking machine, obtain our receipt, and step through the open glass doors. Chemotherapy, here we come.

Everything about the facility is bright, relaxing, and welcoming. If we didn’t know better, we would think we are stepping into the lobby of an upscale hotel. Although the motivation behind the people visiting today is rather grim in nature, we find most of the faces we see to be pleasant and smiling. Volunteers in blue vests wander the hallways offering cups of tea and there are even friendly therapy dogs who seem to instinctively sniff out those who need it the most and sidle up to them in order to offer up their bodies for a snuggle and a few loving pats.

After a brief stop at the information desk, we are directed up to the second floor where we will check in for our chemo session. Of course, I am asked to state the date of my birth (how come everyone in the health field is so interested in my birthday, and yet I’m not receiving any more cards and presents?) and when I answer correctly we are asked to have a seat in the waiting room.

It isn’t too long before one of the volunteers calls our name and escorts us to the chemotherapy clinic. We pass through the automatic doors and enter a large space with sixteen bright blue La-Z-Boy recliner chairs placed around the room. Windows on two sides suffuse the area with natural light and views of several large Garry Oak trees outside. In the centre of the room is the nursing station where nurses attend their duties, which seems to entail a lot of comradery.

We are led to the only unoccupied recliner in the room which had been vacated just minutes before by its last chemo receiving occupant. We half expect someone to hand us the remote and a bowl of popcorn, but out strides Sam, our nurse for this particular round of chemotherapy (he, like all the other nurses have their first names written in felt pen on the front of their nursing tunics). He checks my name, asks me my date of birth (again) and off we go into the realm of chemotherapy.

We tilt back our recliner (we keep saying “we” because remember that you are along for this ride), a little apprehensive since we know that we are going to be poked sooner or later. Sam feels around and soon finds a nice, fat vein in the crook of our right elbow. He brings over a wet, warm towel, and wraps it around the chosen arm so that the vein will puff out even more and be easier to tap.

We are left alone for a few minutes to allow the towel to do its work. As we start to relax, we notice the others who are lying back in their recliners having their individual chemo drugs infused into their bodies from tubes attached to clear plastic bottles hanging from metal stands. Almost all of the cancer patients have friends or loved ones sitting in chairs beside them. My wife, Jane, accompanies me on every trip. Some of the people receiving their chemo infusions are wearing caps, toques, head scarves, or wigs. This is because many of the drug “cocktails” cause total hair loss. We’ve been told that our particular concoction, brentuximab, does not cause the baldness effect, but there is no denying that my hairline has thinned to the point where a hair tie is no longer necessary to gather up my scraggly, greying mane (a single strand of dental floss will now do the job).

Sam returns, removes the towel, and proceeds to carefully direct the intravenous needle into my arm and tape it in place. We look away, just as we always do when having a blood test, but the needle goes in easily and practically painlessly. Sam explains that we will start the I.V. drip with just a saline solution to make sure everything is flowing properly. While this is happening, Sam contacts the Cancer Agency pharmacy to order our chemo cocktail to be readied for infusion. He explains that the drug is very expensive and will not keep once it is prepared, so it is not until the patient has arrived on time and the I.V. is working properly that the drug is actually “mixed together” by the pharmacists.

Before the plastic bag of the actual chemo is connected to the drip line, one precaution must be taken. On the first round of chemotherapy a couple of months earlier, there had been an allergic reaction which manifested itself about halfway through the infusion by creating in me a feeling of nausea, a sensation of extreme heat emanating from deep inside my body, and a severe itching on the entire surface of my skin. To prevent this from reoccurring, Sam now introduces a measured dose of the antihistamine, Benadryl, to the drip line.

It is not very long after that we feel completely relaxed and our eyes begin to droop from the sedating effects of the Benadryl. Dreamland beckons. Suddenly, a high-pitched beeping sound emanates from the machinery behind us and we are brought quickly back to total alertness. Sam returns quickly from the nursing station to check the I.V. line into my vein. As it turns out, our relaxed posture resulting from the antihistamine has made our arm flop over to the side, thereby causing a restriction in the flow of the chemo. Sam straightens our arm, lifts it back on the pillow it has been resting upon, and the warning beeps cease. A volunteer comes by to offer a warm blanket. All is well.

All is well, that is, until we become very aware that we have to empty our bladder and really soon. No problem. The metal chemo stands are on wheels, so we can get up out of our recliner and take the whole kit and caboodle chemo apparatus (although somewhat unsteadily and awkwardly) into the bathroom with us.

Once back in our recliner we notice that the warning beeps are going off every couple of minutes. This is because they signal not only that the drip lines are not acting properly, but also that the entire chemo cocktail has been infused and the session is finished for the particular individual receiving treatment. The nurses pop out from their station, scanning the room to discover which recliner is the source of the annoying beeps. They tend to the problem, or detach the drip line if the treatment has been completed.

Finally, our turn comes up. The plastic bag holding our chemo cocktail is now empty and Sam carefully removes the needle from my arm. We are separated from the metal stand with all its accompanying tubes and bags. In total, we have spent about two hours in the recliner (it would have lasted only thirty minutes had it not been for that earlier allergic reaction and the resulting addition of the antihistamine to the procedure). Others, we learn, are less fortunate and must remain attached to the drip line for seven or eight hours.

As we exit the Cancer Agency building, we realize that we will be returning in three weeks for our next round of treatment. We know there are others fighting more aggressive forms of cancer who must attend more regularly. We smile and make eye contact with everyone as we leave the premises. Their returning smiles confirm the tacit agreement that we are all in this together.

Nobody asked me, but even though I wish I had never been among the unfortunate ones who must be subjected to this experience, nevertheless I am thankful for all the doctors, nurses, medical technicians, ferry crew, friends and family who give me hope for tomorrow.

One more thing. Thanks for coming along for the ride.

About the Author

Shilo Zylbergold lives on a small island somewhere in the southwest corner of British Columbia, Canada. He grows vegetables, teaches math, and is a columnist for a local paper. Send complaints to [email protected]

Introducing Stitches!

Your Path to Meaningful Connections in the World of Health and Medicine

Connect, Collaborate, and Engage!

Coming Soon - Stitches, the innovative chat app from the creators of HWN. Join meaningful conversations on health and medical topics. Share text, images, and videos seamlessly. Connect directly within HWN's topic pages and articles.

.jpg)